Her air is one of independence, but often one is deceived by such airs although her wit will cover her depth to all intents and purposes. Her speech is soft and clear, more inclined to be biting like the salt water. With her hands on her hips, the sea blue eyes will sink into your soul and examine you for what you may be. Her head is thrown back when in her favourite pose. Imagine a tall handsome woman with auburn hair and a fair wrinkled brow. Ward related Peig’s hardships, how her father owned no land whatever, ‘not even the grass of a goat’ and depended on his naomhog, his fishing nets or lobster pots to feed his children. I sat for a moment without speaking and as my eyes stared blankly into the back of the fire, I felt ashamed of myself, in fact ignorant, I was a creature of a many who was much too fond of himself, to live the life of simplicity that these Apostles lived … Bail D’ Dia Ar Earinn – such is the hidden soul of Ireland that seldom is shown to the stranger. Perhaps it was the language in which it was spoken that made it so. It was even more beautiful than I can describe. Peig’s De do Bheachasa rang through the cabin and settled in the depths of my soul.

He found Micheál Sayers and Coady, Peig’s brother-in-law, smoking pipes by the fire, the walls of the neat cabin covered with pictures of students and children, professors and editors, and a church of Scotland bishop, Peig’s ‘best friend’, who visited the Blaskets and remained with her until he had mastered the Irish language. The red-haired, red-bearded poet, who spent much time in Dunquin, described his approach to the gale swept Mount Eagle and to the little cabin with the black felt roof which was tied down with sugones ‘the rocks at the end of them swinging back and forth with the force of the gale’. On a bleak winter’s morning a few years later, Peig was visited by the wandering bard, Eoghan Roe Ward. In 1942, Peig and her son moved back to Vicarstown, the old home place on the mainland. 13 Only Micheál, author of A Pity Youth Does Not Last, did not favour life abroad and soon returned to Ireland where he remained for the rest of his life. Her sorrows were compounded by the emigration of all of her children, Maurice, Padraig, Micheál, Catherine and Helen. In 1923, at the age of fifty, Peig was widowed. In 1901, her 68-year-old mother and 76-year-old father were recorded there on the census. 12Īs far as can be established, Peig’s parents remained in Vicarstown. There her children were born, and there, like her mother before her, many of them did not survive. 11 Peig moved to the Great Blasket Island where she would remain for the next forty years. On 13 February 1892, at the age of 18, an arrangement was made for her marriage to fisherman Pádraig Ó Guiheen, son of Michael Guiheen and Mary Sullivan. 10 Peig was educated at Dunquin National School but at a young age was put out to work as a maidservant in the Dingle area. To the great joy of her mother, who had so heartbreakingly seen her last nine infants die, Peig thrived. They moved in 1872 and six months later, on 29 March 1873, Peig Sayers was born. 8 Margaret Brosnan, now Mrs Sayers, believed that if they moved, their fortunes might improve and so they took up residence in Baile an Bhiochaire (Vicarstown) in Dunquin. 7Īt this time, they had three surviving children, John, Patrick and Mary. They didn’t prosper in Dunquin no more than they did in Ventry … one after another, the children died, until in all, nine children were buried. 6 In her autobiography, Peig recalled that her parents enjoyed six years of prosperity before their fortunes took a turn for the worse:

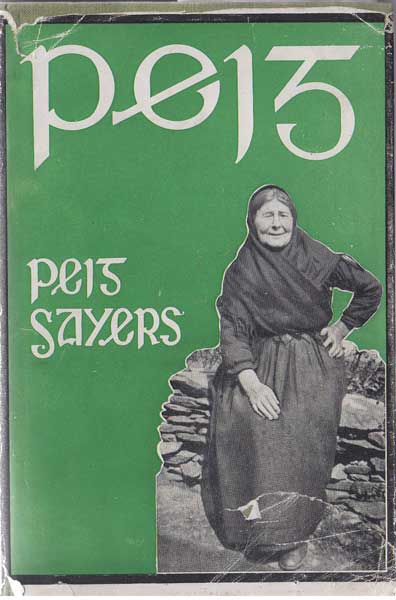

The young couple lived first in Ventry but at some point moved to Dunquin. Tomás Sayers was a farmer, fisherman and storyteller who shared his stories with Jeremiah Curtin 4 He was said to be of Bearla (English) descent (the name of Sayers was not uncommon to the Dingle area indeed, the parents of another Tom Sayers, the nineteenth century champion bare knuckle fighter who defeated Heenan, were from Dingle). 3 If this was the marriage of Peig’s parents, there is little more to add than it was witnessed by Daniel Divane. It is a long road from Castleisland to Ballyferriter but in the latter there is on record the marriage, in 1851, of Margaret Brosnan to Tomás Sayers (or Sears). Peig at her own fireplace in Dunquin c1946 © UCD Tom Brosnan, author of The Brosnan Gathering, remarked that, despite Peig’s international literary fame, little seems to be known about her mother, and her Castleisland forebears appear something of a mystery. It is generally accepted that Margaret Brosnan was from Castleisland.

1 It contains an interesting article about Blasket Island writer, Peig Sayers, whose mother was Margaret (Peig) Brosnan. A Brosnan Gathering is the title of a book produced in 2013.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)